This is where I have been…

The photo is taken on the property where I spent my first five years, in the Gascoyne in Western Australia. I flew across the country, drove north with family for company and stories, and travelled back in time over decades, to find another kind of meseta in the outback.

Now I’m home in Melbourne, beginning to try to make something like sense from the pilgrimage. Time will tell whether or not that is possible. I hold onto the words of T.S. Eliot…

We shall not cease from exploration, and the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time.

It may take forever to find sense, or to achieve any kind of knowledge, but exploration is surely the vital thing, and in one of those curious serendipitous occurrences, we were back on the land where my mother’s ashes are scattered on the very day when the Fairfax newspapers published this piece I wrote months ago. The photo is theirs. I wish I’d looked so glamorous out on the camino roads! You can read the article online in situ, with ads, here if you prefer.

Sun and shadow

- When Ailsa Piper made a walking pilgrimage across the length of Spain, her late mother was a constant companion.

In lock step … the author often felt her mother walking beside her. Photo: Getty Images (posed by a model)

I write this on my mother’s birthday. Mum loved an occasion. Christmas was a day-long fiesta that started at dawn when she woke before we did. Mother’s Day was tea with toast burned by us as she pretended to sleep. Birthdays were top of her pops; she insisted they be celebrated. Her last wish was that every year we raise a glass on the day she was born.

Often I slip up when toasting her birthday and refer to it as the day she died. It’s as though her birth has become inextricably linked in my mind with her death – as though I can’t think of her beginning without remembering her ending. Maybe it’s because I can’t recall her full-force gales of laughter without immediately seeing her reduced to a coiled spring of suffering in a hospital bed.

Mum died almost two decades ago, her hair still dark, and with few wrinkles, although cancer had begun to etch itself into her face. Now, when I think of her, she is birth and death, pleasure and pain, joy and grief, simultaneously.

After a city birth, I went home with Mum to the family sheep station, where my world was bounded by the fences my father regularly rode out to check. Desert country. Unyielding. But Mum gave me other possibilities. Each night, she recited Edward Lear’s The Owl and the Pussycat to me until I fell asleep. She did it for years, until I could recite it back to her.

Surrounded by drought-afflicted soil, she whispered of a pea-green boat bobbing on a star-lit sea. In a place where every drop of water was as precious as platinum, she described lush Bong-tree woods, and a runcible spoon scooping slices of impossible-to-imagine quince. Strange fruits and lands, exotic and enticing. And, of course, there was that impossible couple, owl and cat, dancing under a distant moon.

I know the poem by heart. By my heart and her heart.

Just after I decided to walk 1300 kilometres across Spain from Granada to Galicia, I heard a psychologist talking about the importance of the tales we’re told as children. He believed the best any parent could offer was The Owl and the Pussycat. Think about it, he said. The central characters celebrate their differences, and set out on a great quest, with plenty of all they need: honey and money. The decision to marry is instigated by the cat, and the owl loves her strength. Not a bad template for life.

Some people were dismayed when I part-financed my Spanish walk by selling the two paintings I’d bought with my modest financial inheritance from Mum, but I think she’d have approved. I used her legacy to take myself out into the world, whispering our poem to unfamiliar skies.

One day on the road, in a one-burro pueblo called Laza in the mountains of Galicia, I hobbled with a possibly broken toe into a supermarket and struck up a conversation with the woman behind the counter. We talked about mothers. When I told her that mine had been my best friend, and how I missed her, the woman’s professional face cracked. She said her mother had died only a year before, at the age of 80. I said I often walked with mine; that I still felt her absence, after all these years. Suddenly, we were both crying, hugging like intimates.

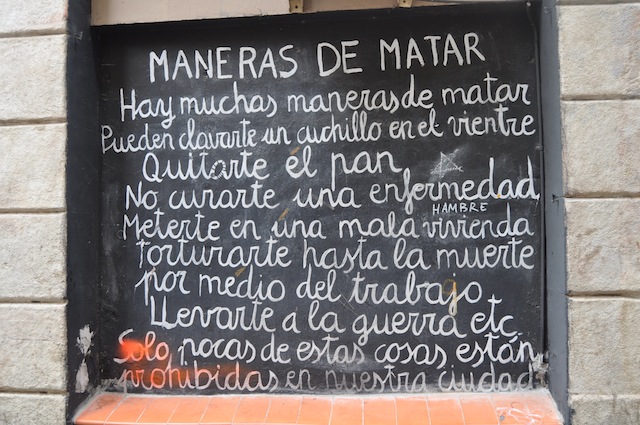

Through her tears, she said life is sol y sombra – sun and shadow – and you don’t value one without the other. She kissed my hand as she gave me my change and I walked into the late afternoon oblivious to the pain in my toe.

Sol y sombra.

I wondered about it as I limped to the town’s cemetery and looked across the gravestones to the surrounding hills. I remember thinking how Mum would have loved it all: the silent grey-stone town, the quince paste I’d bought in memory of the poem, the donkey grazing on lush grass studded with white and yellow daisies, the clouds whizzing ahead to road’s end. The swishing sounds of Spanish. The moss and lichen on granite fences. The mists. The otherness.

Mum never got to go to Europe. Sometimes I think my yearning for the road is in part a wish to wander on her behalf, a quest for Bong-trees.

“Sol y sombra,” I whispered, my bones aching for heat in that cemetery swirling with winds blowing chill from the north.

Sun and shadow.

I think the lady in the shop was right. We do value the sun more when we have known shadow. Why is that? I refuse to believe suffering is necessary for happiness, but it certainly puts it into sharper relief. I don’t want to believe I love my mother more for having lost her, but it makes the love, all loves, more precious.

Later along that road, I learnt the Spanish have a drink called sol y sombra. It’s equal parts brandy and anise. Not for the faint of heart. Maybe next year, on Mum’s birthday, I’ll shout myself a glass of sol y sombra and drink to the sunshine Mum gave me to navigate through shadows. Maybe I’ll raise a glass on the anniversary of her death, too.

No. Why wait? Loss teaches us to seize our days. I’ll find a sol y sombra tonight and raise it to love.

Serendipity.

Coincidence.

They always make me feel that I’m in the right place, even if that is nothing more than projection of my own hopes. No matter. It was a camino, I was a pilgrim, and I think the road is leading me somewhere. I’ll keep you posted!

Meantime, there are a few events coming up between now and Christmas, all of which will be listed on the “Events and Media” tab above, and updated on Facebook.

Did I just write Christmas? Ay caramba!

Thanks as ever for subscribing, and for your support and comments. And if you are a first-time visitor, welcome! Bienvenido! You might like to click on the “AAA – my favourites” link on the right to get a sense of the journey so far.

Hasta pronto, compañeros.